Munud i feddwl: Beth mae Duw yn gofyn i fi wneud yn y sefyllfa hwn?

This week I went to see the film Elvis. I’m of the age that Elvis Presley was still quite an influence but had died by the time I was about eight. I was surprised by how much I didn’t know about him, especially his musical influences, particularly black artists, in a world which was still segregated and openly and violently racist. At the same time, I was listening to James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree on audiobook as I was driving, a book which has had a profound influence on me.

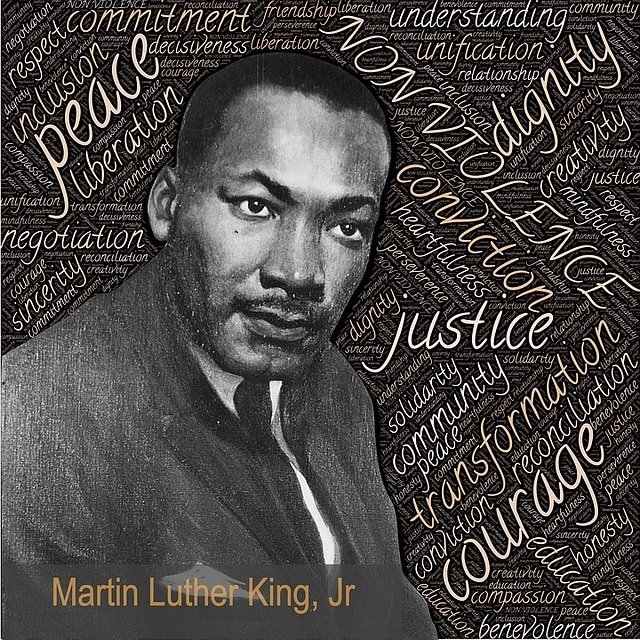

So I’ve found myself living in two worlds, the world of my everyday life - working at St Padarn’s and going about my chores at home in 21st century Wales and finding my mind wandering to 20th century America and the events which happened before I was born but which still has a continuing impact on us - the assassination of Martin Luther King, the fight for civil rights, even the phenomenon of celebrity and how numerous people like Elvis Presley who found the experience initially exciting and transformative only to find it destroyed them.

James Cone argues that white clergy and white theologians failed to make the connection between Jesus’ crucifixion and the horrific lynching of black people in the United States, despite its clear and obvious resonances. He criticizes white theologians particularly for choosing their own safety and comfort over speaking out for the freedom and safety of black people. It struck me particularly his point that Martin Luther King risked his own life every time he spoke, because he had received several death threats. And yet, white clergy and theologians at the time lived their lives in relative safety and comfort. However, he does single out one theologian who went out of his way on a visit to the US to understand the black experience – unsurprisingly it was Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

When my mind has wandered back to my own time and my own context it has made me think how easy and safe it is for me to be a theologian and an ordained minister. I may get nervous before I preach or speak at an event, but that maybe to do more with wanting to come across well. I don’t have to contend with fearing for my life every time I open my mouth in public.

In Nazi Germany, and South Africa under apartheid and dozens of other political situations churches have openly shored up oppressive regimes. In our own country, the church is told to keep its nose out of politics and concentrate on spirituality, as if spirituality is separate from justice and action.

I still need to reflect on my learning this week, but it has struck me that our 21st century world is not so different from that of the 20th. Celebrity still ruins lives, and it is still dangerous to be the wrong person, in the wrong place at the wrong time. What can we do to stand up for those who are oppressed in our nation and across the world? And is there evil being perpetuated that theologians, ministers and the church are just accepting?

This is why theological reflection is so important. Our alternative name for our BTh course is ‘Theology for Life’. This conveys that we think theology is not just for academics or clergy but for everyone. But theology should challenge us, not make us comfortable and should always lead us to the question what is God asking me to do or say in this situation?

Parch Ddr Manon Ceridwen James